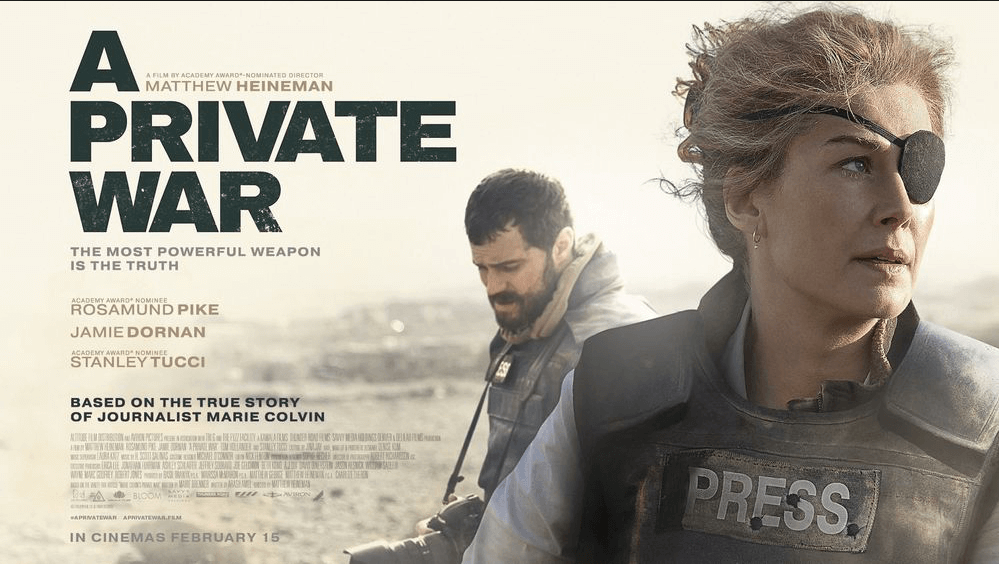

Review: A Private War depicts the glamour and gore of the life of a legendary war correspondent

25th February 2019

“You’re never going to get to where you’re going if you acknowledge fear. I think fear comes later, when it’s all over.”

The words of the legendary war correspondent, Marie Colvin, in her coarse American tone, cut sharply through harrowing shots of the city of Homs, Syria – the place which was to be her final story – as A Private War begins to roll. Directed by Matthew Heineman, the biographical drama, based on the life and work of the celebrated Sunday Times reporter, is summed up accurately by his preferred description of the film as “a psychological portrait of Marie Colvin”.

However, it is also a portrait of the many faces of war. “War is the quiet bravery of civilians who will endure far more than I ever will,” Colvin is quoted as saying in the film. A Private War is a sharp – at times almost physically painful – reminder of the human cost of war.

Just as Colvin strove to do through her work, the film gives a face to the real victims of warfare, a voice with which to speak of their suffering. The use of Syrian refugees as extras in some of the film’s key scenes makes them all the more powerful and authentic.

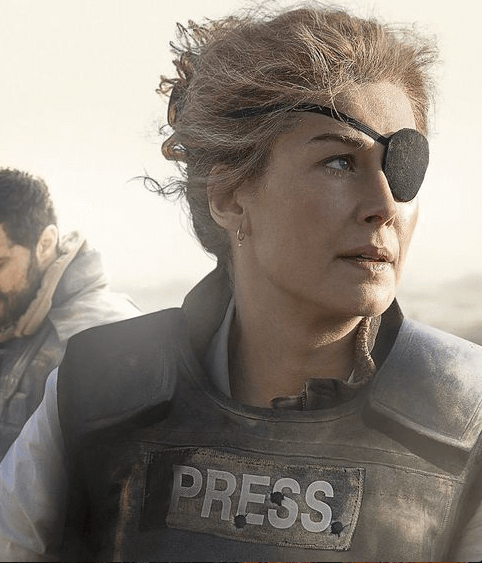

Rosamund Pike (Gone Girl, Hostiles) takes on Colvin’s character with conviction and pulls off a convincing portrayal, rife with complexities and contradictions. From the iconic eye patch, which became her trademark after losing her left eye in Sri Lanka, to the La Perla underwear worn religiously under her flak jacket. “I hate being in a war zone, but I also feel compelled to see it for myself,” says Pike as Colvin. She saw children starving, yet dieted profusely so as not to get fat. She was afraid of growing old, but also of dying young. She had suffered two miscarriages, but still wanted to be a mother.

The film flicks impatiently, from one war zone to the next, while scattered snippets of Colvin’s tumultuous life in London lie in between. We are taken abruptly from vodka-fuelled dinner parties to dead bodies, from award ceremonies to military camps, as Colvin defies the concerns and objections of friends, lovers and editors to go to any lengths necessary to get the story.

But it comes at a cost. The inner conflicts, which war reporters themselves must battle, are a key theme throughout the film. Colvin’s diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, after suffering from relentless flashbacks and nightmares, gives a glimpse into the psychological toll war takes on its reporters and the sacrifice they make for the truth. However, while we are made acutely aware of Colvin’s mental conflict, the film only briefly touches on the natural flaws of her character, preferring to depict her as the hero uncovering mass graves, rather than the alcoholic embarking on one-night-stands.

The use of the timeline of dates leading up to Homs, 2012, when Colvin was tragically killed, is more troubling. It feels almost as though we are counting down to her death as the most important event, rather than acknowledging that actually, the most interesting thing about Colvin is what she did while she was alive.

The film throws up many observations of the press. How the world responded to journalists changed beyond recognition over the course of Colvin’s career, since that her dispatch as a foreign correspondent in the 80s. When she came under fire in Sri Lanka she held up her hands and shouted “journalist” for protection. In a war zone, the press badge once could have saved your life; by the time Homs came under seige in 2012, it was the very thing that would get you killed.

With her one good eye, Colvin saw more than most do in a lifetime. She faced the horrors of war up close, so others didn’t have to.

In an age when social media and fake news seem close to threatening the relevance of journalism, A Private War reminds us of the need for professional reporting.

Colvin’s commitment to the truth represents what journalism stands for – and what many enter the field striving to achieve – to uncover injustices, to tell human stories, and ultimately, offer up the truth. And seven years after her last broadcast, you could say that this has never been more necessary.